The Mangels/Pflugeisens of Tarnow in the US, Poland, and Austria; The Silver/Leibens of Russia and the US

Marc Mangel

Current version: March 2021

Motivation

In fall 2012, I converted an approximately 25 year old interview that a friend of ours conducted with my father Karl Mangel. Karl came to the US in 1939, from Austria (which he left after the Anschluss) via Belgium, sponsored by Sol Mangel. His surname then was Pflugeisen, which he changed in 1947 after he married my mother (Ruth Silver, who changed her name to Barbara Mangel). In the interview my dad simply sad that his father had a lot of relatives in the US. I set out to discover the connection between the Mangels of the US and those of Austria. Growing up, my brother, sister, and I could not fully understand the surname issue and I also set out to resolve that. In this, I have been helped greatly by Thomas Vedel Janhøj, who lives in Copenhagen and who is descended from another Pflugeisen, so we are not related (at least to the great-great grandparent level).

I have also started to work on the history of my mother’s family: her father was David Silver and her mother Rebecca (Bessie) Leiben. I first provide information about the paternal line (since this was the motivating puzzle) and then the maternal line.

Although I had previously done my DNA analysis with Ancestry and 23 and Me, because of a special from My Heritage, I recently redid the analysis. It turned up as 90% Ashkenazi and 10% Middle Eastern (5.2%), North African (3.0%), and Iberian (2.0%). That is very cool.

PATERNAL LINE

Results for the US

My research thus far has determined that the most likely common Mangel ancestor in the US was Max Mangel. Max was born in Tarnow, Poland which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian (AH) empire, in March 1848 and immigrated to the US in June 1883. [He applied for a passport in April 1906]. A July 1906 manifest for the Port of NY lists his address as 734 5th NYC. (There is also somebody called Louise Mangel, 729 5th on the manifest.) When Max was naturalized on 22 Oct 1892, he listed his occupation as pedlar and former nationality as “Emperor of Austria”.

Max, Sol and Simon. The NY 1925 census lists Max as head of household (at age 75) living in the Bronx and members of the household are Marian [Miriam] Mangel (50), Annie Werner (47), Hernym Hochberg (32), Sadie Hochberg (27), Mitchell Hochberg (4) and Harrell Hochberg (0, by which I assume infant). Max is also in the 1915 NY census and the 1900, 1920 or 1930 US census. I have not yet had time to follow up on the Hochberg family.

Max’s obit (25 Nov 1934) lists him as the husband of the late Miriam and dear father of Simon, Solomon (whom I knew as Sol), Rose Mangel, Ester Ehrlich, Sophie Lacov, Lottie Granovetter, Anna Werner, and Sadie Hochberg.

The 1940 US census lists Morris Hochberg (aged 45), Sadie (age 44), Mitchell (19), Ruth (15), and Anna Werner (60) as sister in law.

The most information concerns Sol. The 1910 census lists his birth year as 1882 and his wife as Jennie [also called Jenny] nee Dimand, born 1894. [Interestingly, both Lucy Taubenblatt Laposky and I named daughters Jennifer.] They married in 1905, so I expect that Jennie’s birth year in the census is off by about a decade. Sol’s WWI and WWII draft registrations give his birthdate at 5 Sept 1881 in Tarnow, Poland, consistent with Max’s immigration date..

Sol appears in the 1920, 1930, and 1940 census. There is a lovely article from the NYT on 21 July 1956 about Sol and the Mangel stores; I am happy to send it to anyone who wishes. Sol had three children: Deborah, Sidney, and Emanuel.

Sol’s daughter was a debutante and high flier. She graduated Wellesley in 1937 and got a Master’s from Columbia. She married Herbert Dietz, a lawyer, on 23 Nov 1939 at the Waldorf-Astoria. Their wedding got about 1/3 a column of coverage in the Yonkers Herald Statesman with a nice picture of her in bridal gown. Dietz did his undergrad at City College and law degree at Harvard. She was deeply involved in Democratic politics and a supporter of Brandeis University. Deborah died 16 April 1960 at age 43, so she was born in 1917 (thus contemporaneous with Karl). She was survived by her father, both brothers, her husband, and son Roger. I found a Roger Dietz who is a lawyer in NYC with what would seem to be the right credentials and age, but he has not responded to my email message. Deborah had a daughter, Peggie Dietz, whom I am still trying to find.

Jennie Mangel’s obit is 21 Feb 1947, which claims her age to be 64 (a little bit inconsistent with the 1910 census).

Just after Pesach 2015, Ittai Hershman wrote to me about a window at the Community House Chapel of Bnai Jeshurun dedicated to Sol and Jennie Mangel. It’s the upper right in the panel of windows in front of the Ark:

The photo is online at: http://bjnyc.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/DSC05070-e1425392203241.jpg. BJ is on the North side of 88th Street between Broadway and West End Avenue. The community house is a separate structure on the South Side of 89th. Visit it if you get to New York.

I also found an obit for Martin Mangel, son of Emanuel and grandson of Sol, from 6 March 1949.

I last met Sol in 1969. His obit is 27 Oct 1972; he died at age 90. He was survived by his widow Betty, sons Sidney and Emanuel, and three grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. Sol is buried in the Mount Lebanon Cemetery, 7800 Myrtle Ave, Glendale, NY [info@mountlebanoncemetery.com]. The obit for Sol’s second wife, Betty, is 15 Mar 1995.

Simon’s obit is 4 June 1953. It describes him as husband of Annie (I have yet to track her pre-marriage surname), father of Regina Taubenblatt (and thus grandfather of Leonard and Sylvia), Theresa Seiken, and Selina Sarel. He is, of course, described also as brother of Sol, Annie Werner, Ester Ehrlich, Lottie Granovetter, Sadie Hochberg, and Sophie Lacov.

The 1915 NY census lists Annie Werner as born in Austria about 1889 (her age in the census is 26). This would suggest that Max may have returned to Tarnow at least once and had family there (he did get a passport, after all); alternatively Annie may have been older and the census report inaccurate. Annie was married to David Werner (age 27) with one child Esta Werner. Also listed at the household for the census are Sarah Henig (age 23) and Bella Henig (age 21). The census also lists all of their birthplaces as Austria.

In March 2015, Mark Granovetter (grandson of Lottie), who lives in Palo Alto, and I established contact with each other. As I will explain below, I believe now, but have not proven, that Sol and my grandfather Markus Pflugeisen were first cousins, thus providing the link between Mark (and also his cousins Matthew Granovetter in Cincinnati and my erstwhile colleague at UC Davis Jeff Grannett) and me.

The Gold Family On 16 Dec 1896, Hester (Ester?) Mangel married Morris Gold, both giving their country of birth as Austria. They appear in the 1900 Federal census with daughter Rebecca (born 1897; our cousin Reba with whom Karl lived), son Milton (born 1899) and daughter Ester (born 1900). However, it is highly unlikely that an Ashkenazic Jewish woman would name a child after herself. I suspect that the 1900 census entry was an error and that “Ester” was actually Isaac, who shows up on later censuses.

For example, in the 1910 Federal Census the family is Morris and Ester, Rebecca (age 12), Max (10), Isaac (8), Isidore (6), Louis (4), Ella (2), and Joseph (5/12 – that’s how it is recorded in the census).

Morris and Ester were prolific. The 1915 New York state census lists Morris and Ester and then Rebecca (17), Max (16), Isaac (13), Isie (11), Louis (9), Joseph (5), Annie, (8), and Pinkus (3).

The 1920 Federal census lists them and their children Reba (Rebecca, aged 22), Ike (Isaac 18), Isidore (16), Louis (14), Anna (12), Joseph (10), Phillip (7), and Ruby (4). Ruby was thus my father’s age, and my sister Debbie remembers commenting to my Dad at her wedding (1980) that Ruby was such an old guy, and Dad was upset since they were the same age.

The 1925 New York state census shows that Reba (then 27) had married Michael Rich (29) and had one son, Maurice (1).

By the time of the 1930 Federal Census, Irving Gold is listed as the head of the household, at age 28 so it is likely that this was in fact Ike who should have been listed. Living with him are Isidore, Morris, Anna, Joseph, Phillip (listed as Paul), Rubin (Ruby), Ester (Mother, aged 54), and Reba Rich and her son Murray (age 5). It is likely that Reba had married and widowed (possibly divorced); I need to work on that.

The 1940 US census shows Reba as the head of the household, and lists everyone else as “lodger”. These include Isador Gold (age 35), Anna Gold (age 21), Rubin Gold (age 24), Murray Rich (age 16), Carl (sic) Pflugeisen (age 23), and Celia Mangle (sic?) (age 60). Celia listed her birthplace as Austria, but I have thus far not been able to find anything more about her.

Results for Austria and Poland

A colleague on the Gesher-Galicia SIG at Jewish Gen gave me the following information on the names Mangel and Pflugeisen in Galicia:

MANGEL (German for, lack, or fault.). Other variations seem to be: Manger and Mangler. Found in: Krakow, Nowy Targ, Nowy Sacz, Tarnow, Rzeszow, Kolbuszowa, Lancut, Lwow, Kolomya, Rohatyn

PFLUGEISEN (from the German for iron plow; also FLUGEISEN) Found in: Krakow, Tarnow, Kamionka, Lwow

Results for Austria.

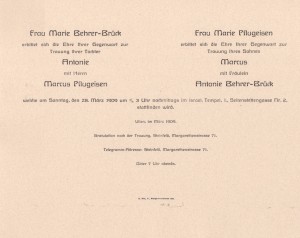

On 28 March 1909, my grandparents Antonie (Toni) Behrer-Brük (Brueck) and Marcus (Markus) Pflugeisen were married. Here is their wedding invitation

Toni’s birth record gives her surname is given as BEHRER, not BRUECK

Her father was Moses Josef Behrer from Lemberg (alternately known as Lvov or Lviv — see the wonderful book East West Street by Phillipe Sands) in the Ukraine; her mother was Marjem (commonly known as Marie) nee Menkes. Although shown as legitimate (i.e. their marriage is recognized civil authority), there is a note about the birth being legitimized, and some writing is too faint to decipher.

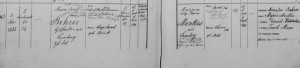

Here is the marriage record of Marcus and Toni

The details are these:

- The names of both mothers was Marjem (Miriam)

- There is no mention of Marcus’s father’s name. As above, it is likely that his parents had a religious wedding, without it being recorded by civil authorities.

- Markus was born on 1 November 1880 in Zbylitowska Góra — a small town about 4 miles from Tarnow, where Max Mangel came from. (Immigrants often reported a larger, better known town as their place of origin.)

- The bride’s name was given as Toni BRUECK, no mention of BEHRER.

- Toni was born in Vienna on 27 January 1883.

Toni died on 31 Dec 1938, at age 55, and Markus died at age 59 on 11 Dec 1939. Thus, they are both contemporaneous of Sol and Simon. For those planning to travel to Vienna: Markus Israel Pfluegeisen is buried in Section t4, Group 4, Row 29, Grave 57. The Cemetery address is XI. Simmeringer Hautpstrasse 244 and immediately comes up in a Google Maps search.

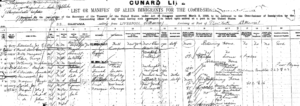

I have found a record of Julius’s birth in 1910 (but neither of Karl, my father, or Mary, my aunt, because the Austrian records on line stop in 1910), of Karl on the passenger list sailing from Antwerp on 28 Oct 1939 and arrival in New York on 10 November 1939, indicating that he will join Sol Mangel at 1115 Broadway.

I have found considerable information about Toni’s family. This is part of a family tree that I found on Geni.com, by through a search that lead me to Julius Pflugeisen (I later put in the details about Karl and Mary). If you cannot read it, write to me and I will send it to you

and here is the remaining part

I will discuss great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents when I come to Poland, but for now we stick with Austria.

Toni came from a large family with many sisters. When her sister Emeline died in 1918 (presumably of the flu), the obituary listed all the sisters and their spouses. They were:

Anna Rebekka Steinfeld (born 1881); Antonie Pflugeissen (born 1883); Fanni Steinfeld (born 1887); Minna(short for Wilhelmina) Muillmann; Lotte (short for Charlotte) Behrer (born 1890); Emma Behrer and; Ernestine Behrer (born 1892)

This accords with Karl’s memory that his mother had 7 sisters (one of whom, since he was born in 1916, he would not have known).

Anna was married to Arnold Aron Steinfeld, Fanny to Josef Steinfeld (but see below), and Minna to Simon Muillmann. When Ernestine died during the flu pandemic in 1918, some of the married couples had children (the obit mentions “saemtliche Neffen”, which is technically all nephews but usually means all nieces and nephews). One of the children of Ana and Arnold was Julius Steinfeld (b. 1901, d. 1971), who was thus a first cousin of Karl. Their two other sons were Mathias and Karl. Based on their death dates of 1942 at Geni.com (https://www.geni.com/family-tree/index/6000000020817731614), as explained below, they were murdered by the Nazis.

Marc Steinfeld’s Research

My cousin Marc Steinfeld is the grandson of Arnold Aron and Anna Rebekka; his father was Julius, who had brothers Mathias and Karl. Marc has also done work on family history and graciously allowed me to include his research on this page. We begin with a map of Galicia in 1914

Aaron Steinfeld (born 1877) and his brother Oskar (birth-date unknown) decided at the age of 15 or 16 to leave Lemberg for Vienna. Poland in that time was part of the Austrian Hungarian Empire. Life in Poland at the end of 19th Century was very hard and difficult. The economic situation was mostly catastrophic. Poland was an agricultural country and its industrial development was far behind other European countries such as Germany, France, or Great Britain. Jews in Poland often experienced anti-semitic riots, which provided another reason for leaving Poland. At the end of the 19th Century, Vienna was one of the most attractive cities worldwide. It is no wonder that young people were especially attracted by this lively and vivid city and tried to settle down in Vienna.

Even so, at 15 or 16 years old, Aaron and Oskar must have been very courageous to make such a big step. Even though Vienna was not too far from Lemberg, so that there was a possibility of returning, it was clearly a risky decision.

It is not clear where Aaron and Oskar stayed after arriving in Vienna; maybe they had friends who had earlier left Poland, but it also seems that at this time the Jewish communities and welfare organizations were organized and therefore, it could be that two such courageous and adventurous young men were welcomed with open arms. Marc believes that both of them apprenticed as shoemakers (maybe they already started doing it in Lemberg), and soon could upgrade themselves as merchants. Contrary to many other eastern European immigrants, especially the very religious ones, they quickly integrated into the Austrian lif e and society.

Aaron and Anna Rebekka Behrer (born 10.10.1881 in Vienna) married around 1898/99. By this time, he presumably had already financial resources to start a family. Their eldest child, Julius, was born on 21 Aug 1901. Two more children followed, Matthias born 28 May 1905 and Karl born 03 December 1909.

A few years after Julius’s birth, Aron and Oskar decided to establish their own companies and shoe shops. They had a business partnership, which lasted until the Shoah, each with his own company and shop. Aron founded his company in 1907. It had to be established in the name of Anna Steinfeld-Behrer, because since he was born in Galizia, Aron did not have Heimatrecht in Vienna, which would give him the right to do whatever he liked. The shops were quite succesful, so that the family rose in social class and their boys could choose whaterver school they liked. All three boys graduated from high-school; Julius began his studies at the University of Technology, but decided after a few semesters to enter into the family business and followed his brother Matthias in this way. Karl studied medicine at the Vienna University, finished his studies around 1934/35, and worked in Vienna as internist.

In 1932, Julius married 1932 Rosy Guttmann. Rosy was born in Rzeszov, Poland, on 17 April 1909, and came with her parents (David Guttmann and Bluma Guttmann-Brünner), her elder sister Anna and her brothers Adolf and Moritz, to Zurich, Switzerland in 1910. Matthias Steinfeld married Margarete, nee Benedig, and worked at Aron’s company until 1938. Karl Steinfeld never unmarried. Working as internist, he started his own medical practice at Aron’s home, Reinprechtsdorferstrasse 56, Vienna V.

Although Oskar is not a blood relative, his story — as told by Marc Steinfeld — is sufficiently interesting for me to include. Marc Steinfeld thinks that it is possible that Fanny Behrer, Anna’s sister, could have been married to Oskar Steinfeld. In this case, two sisters of the Behrer family would have been married to two Steinfeld-brothers. Unfortunately, Julius never talked about it with Marc. Nor did the late Fanny Ziegler(- Steinfeld), child of Oskar Steinfeld. Oskar survived in Vienna during the war (he was the only surviving member of the family still living after 1942 in Vienna). According to Julius Steinfeld, it appears that Oskar was hidden by somewhere in Vienna. Unfortunately we do not know the name of these brave people. Just before the end of the war, he suffered a stroke which he only survived for a few months. He appears to have died just after end of war 1945 in Vienna, with the story of his survival un-recorded.

A few photos

Anna Steinfeld-Behrer and Rosie Steinfeld, in Vienna around 1935:

Matthias and Margarete Steinfeld in Venice, around 1935:

Anna Steinfeld and Marie, her housekeeper who lived with Aron and Anna from about 1910 to 1938, and hid them from 1938 to 1942:

Julius and Karl Steinfeld in Tours, around 1942:

Marc Steinfeld’s grandparents; left to right: Anna Steinfeld, Bluma Guttmann, David Guttman, Aron Steinfeld, around 1935

Jews In Vienna 1938-1942

I encourage everyone to read the books by Philippe Sands East-West Street and The Ratline and to watch his documentary A Nazi Legacy (available at iTunes and Amazon).

Normal life ended for Austrian Jews on March 13th 1938 when Hitler marched into Vienna. Only one or two days after Hitler’s famous speech on Vienna’s Heldenplatz, declaring the Anschluss and Austria’s includsion in the Third Reich, many Jewish shops were stormed, marauded and some of them even destroyed completely. This included the Steinfeld shoe shops. Julius told Marc that he was forced by a fanatic crowd, crying antisemitc maledictions, to clean sidewalk in front of the house at Reinprechtsdorferstrasse 56 using a toothbrush.

The famous Austrian writer Carl Zuckmeier described these days “Als wärs ein Stück von mir” (As if it were a piece of me).

“An diesem Abend brach die Hölle los. Die Unterwelt hatte ihre Pforten aufgetan und ihre niedrigsten, scheusslichsten, unreinsten Geister losgelassen. Die Stadt verwandelte sich in ein Alptraum-Gemälde von Hyronimus Busch. Lemuren und Halbdämonen schienen aus Schmutzereien gekrochen und aus versumpften Erdlöchern gestiegen. Die Luft war von einem unablässig gellenden, wüsten, hysterischen Gekreische erfüllt, aus Männer- und Weiberkehlen, das tage- und nächtelang weiterschrillte. Und alle Menschen verloren ihr Gesicht, glichen verzerrten Fratzen: die einen in Angst, die anderen in Lüge, die anderen in wildem, hasserfüllten Triumph………….. Was hier entfesselte wurde, war der Aufstand des Neids, der Missgunst, der Verbitterung, der blinden böswilligen Rachsucht – und alle anderen Stimmen waren zum Schweigen verurteilt.”

Google translate renders this quotation as

“That night all hell broke loose . The underworld had opened their doors and let go of their lowest , most horrible , unclean spirits . The city turned into a nightmare painting by Hieronymus Busch . Lemurs and half demons seemed crawled out Schmutzereien and risen from swampy burrows . The air was filled with an incessant shrill , deserts , hysterical screams from men’s and women throats , the weiterschrillte days and nights . And all people lost their face , equalized distorted faces : the one in fear , the other in a lie , the other in a wild , hateful triumph ………… .. What was here unleashed the uprising of envy, resentment , bitterness was , the blind malicious revenge – and all the other voices were silenced”

On August 25th 1938, Aron Steinfeld’s shops were confiscated by the Nazis; the rest of the family assets followed shortly thereafter. Around 1940, Anna and Aron Steinfeld had to leave their house at Reinprechtsdorferstrasse 56, where they lived for 30 years, and move to an appartment at Beatrixgasse 3. From 03 April 41 until 21 December 41 they lived at 4, Brahmsplatz 2/2, and from 23 December 41 until 02 June 42 they lived in a shared apartment (Gemeinschaftswohnung) at 2 Rembrandtstrasse 24/6/16. Margarete Steinfeld (wife of Matthias Steinfeld) lived with Anna and Aron at least during the last months or year.

What it meant to live in a Gemeinschaftswohnung or Judenhaus, which is what it was called in Germany, and continously moving from apartment to apartment was beautifully described by Victor Klemperer (a famous professor of Romance language and literature who lived in Dresden) in his book I Will Bear Witness, Volume 1: A Diary of the Nazi Years, 1933-1941 (which is available from Amazon, Netflix, etc).

On 2 June 42, in the eighth train to Minsk, Anna, Aron and Margarete were deported and immediately murdered at Maly Trostinec. All deportees were according to SS bureaucracy “Aussiedler” or “Evakuierungstransport”, were handed over by Alois Brunner on the Aspangbahnhof at Vienna. According to “Erfahrungsbericht des Schutzpolizei-Begleitkommandos” these 800 deportees travelled via Braclav/Lundenburg, Olmütz, Oppeln, Warsaw until Wolkowitz where they had to change the coaches to livestock wagons and then were transported to Minsk.

The homepage of the Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance describes Maly Trostinec as follows:

“Deportations to the “Reichskommisariat in the East”, 1941/42

“After the first phase of deportations to Minsk from the “Reich” and the “Protectorate” ended in November 1941, a total of 16 trains with more than 15,000 people arrived in Minsk between May and October 1942 from Vienna, Königsberg, Terezin [Theresienstadt] and Cologne. In accordance with an order from the chief of the security police and from Reinhard Heydrich of the security service, the deportees were murdered immediately they arrived. A pine forest a few kilometres from the former collective farm estate of Maly Trostinec was chosen as the execution site.

“The sequence of the executions always followed the same pattern. As a rule, 80 to 100 men, inclusive of the police force and members of the “Waffen-SS”, were used. After the trains arrived at the freight station in Minsk, usually between 4 o’clock and 7 o’clock in the morning, a group of commandos from the security police took charge of unloading the newly-arrived passengers and their luggage. Thereupon the arrivals were taken to a nearby collection point, where another group of commandos dealt with taking away all the Jews’ money and valuables. At this collection point, members of the security police selected those few people – between 20 and 50 per transport – who seemed suited to being used as forced labour on the Maly Trostinec estate. The deportees were finally driven on heavy goods vehicles from a loading point on the edge of the collection point to the pits about 18 km away. This sequence of events remained unchanged for the first eight transports. From August 1942, the trains were routed over a branch line into the immediate proximity of the estate, where henceforth more unloading and selections took place.

“The deportees on the first transports were shot at the pits. From roughly the beginning of June 1942, three “gas wagons” were also used.

Out of a total of about 9,000 Austrian Jews deported to Maly Trostinec, there are 17 known survivors.”

Philippe Sands’s books East West Street and The Ratline also describes events at Maly Trostinec.

Mark Tritsch (mft_krokodil@gmx.net) posted the following on the Gesher-Galicia SIG on 12 April 2015 in response to the question “Who could leave Austria between 1938-1940”:

“Just a little elaboration on Wolf-Erich Eckstein’s response on this question: we see it all now with hindsight, but not everyone in Viennarealised at the time (or wanted to realise) how desperate the situation was. Reading about Viennese families after the Anschluss, one is often faced with the question, ‘why didn’t they just leave?’

“Many delayed their escape, because they wanted to not just leave, but also take something with them apart from the clothes they were standing up in. That was difficult, as Nazi laws forced Jews to leave everything behind and ensured that when they crossed the border they were immediately recognized by the big red “J” stamped in their passport and had their baggage thoroughly searched. This meant that it was sensible for Jews to avoid or delay at all costs having the “J” stamp put in their passport if they could. One method was to claim a (fictive) Aryan grandparent in Czechoslovakia – it took so long to get the (actually non-existent) documents that one could gain several months to arrange an escape and a way of getting valuables out.

“Another more common method was to be part of the ‘Gildemeester-Auswanderungshilfsorganisation’. This was a Gestapo-sponsored ‘charitable’ organisation that took most of your property and left you with a little, with which you could escape. The proceeds from what was confiscated went partly to finance the escape of poor Jews, the rest went to the Gestapo.

“Many families with children concentrated on getting them out first, hoping to arrange their own escape later if necessary – many children left with organisations like the Kindertransporte or were sent independently to relatives abroad. Those over 16 (too old for the Kindertransporte) made their own way with the little cash they were allowed to take with them to Antwerp etc. By the time the deportations started it seems that most of the Viennese jewish children had been gotten out one way or another.

“But far too many Jews who could have escaped waited far too long. Some of them were old and couldn’t face moving and others (especially women) stayed because they wanted to care for their elderly parents. But there were also those who loved Vienna and just didn’t want to leave. They didn’t want to believe their neighbors were capable of such evil. This attitude is often described with contempt today, but I think we should have at least some respect for it, even if it was very, very foolish.”

The Escape of Julius and Rosie Steinfeld to Switzerland

Julius and Rosie decided to emigrate in May or June 1938. They didn’t see any chance of continuing to live in Austria. They tried to convince Aron and Rebekka to join them. Aron insisted that he was an Austrian, and that the current events would not last for a long time. Rebekka did not want to leave him alone. According to my father Karl, the sisters did not want to emigrate unless all of them could go together and they too thought that this was just another episode of standard Austrian anti-semitism. The sisters had experienced such Austrian anti-semitism their whole lives. For example, in 1901 the mayor of Vienna was a rabid anti-semite (see Sands’s The Ratline).

Before they were allowed to travel abroad, Julius and Rosie had to pass the “Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung” (which was located at the Rothschild-Palais) to obtain permission to emigrate ; at this time it was managed by Adolf Eichmann. During his trial in Jerusalem, 1961, Eichmann stated that he had no anti-semitic feelings and conducted his reviews for exit objectively.

Julius observed that those who had to pass this office, were harassed and subject to anti-semitic attacks, not by Eichmann himself, but by his assistants: Alois Brunner and others. Some of them were very cruel and even violent. Julius observed that during the visit at this office, some people were picked out and disappeared into special rooms. Some time later, these people came out, some of them trembling and others with bloodied faces.

Julius and Rosie first travelled to Switzerland. Even though Rosie lived in Switzerland for more than 20 years before her marriage, had attended Swiss schools, and had an official permit to live in Switzerland before marriage, they were told that they had to leave Switzerland. In August 1938, they emigrated to France and settled in Tours, in the southern part of France.

At first, they were able to run a little shop. However, after a while Julius had difficulties with the officials, since he was a foreigner. Between October 1939 and May 1940 he was detained as so called as an unfriendly foreigner at Camp du Richard. In the officials documents, Julius described it as follows : “ab August 1938 bis September 1942 habe ich mich in Frankreich aufgehalten, interniert in der Zeit vom Oktober 1939 bis Mai 1940 als feindlicher Ausländer im Camp du Richard.” (“I stayed in France from August 1938 to September 1942, interned from October 1939 to May 1940 as an enemy alien in the Camp du Richard.”)

In June 1940, the Germans invaded France and the situation for Jews in France changed dramatically both in the occupied French territories and in the “non occupied territories. In order to escape the imminent danger of detention and deportation, Julius joined the French Foreign Legion. He was sent to Algeria, where he stayed until around August or September 1941. At this time he left the Legion, and returned to Tours. Since her husband was serving in the French Army, Rosie was protected from detention and able to continue her normal life at Tours.

After 2 June 1941, the situation for Jews in unoccupied France deteriorated.

On 27 Sept 41 the German administration staff put a new regulation into effect: The “Erste Judenverordnung” [First Jewish Regulation]”, which brought dramatic cuts into the life of Jews in free France. From then on, Jews living in unoccupied France were forbidden to return to occupied France. A “ein Judenregister”[a Jewish Register], “Kennzeichnung der jüdischen Geschäfte” [Marking of Jewish shops] and “Erfassung des jüdischen Besitzes” [Acquisition of Jewish property] all followed.

Around the end of 1941/beginning of 1942, Karl and Matthias Steinfeld arrived in Tours. According official documents from 1939/40, Karl was registered in Austria “als abgemeldet nach England” [deemed to have left for England]. If he really had a permission to emigrate to England, it’s hard to understand why he returned to Central Europe. Another question for which Marc Steinfeld has no answer is why Matthias’s wife, Margarete, remained in Vienna. Margarete stayed with Aron and Anna Rebekka until the end. (Philippe Sands tell a similar story about his grandparents in East West Street, with very interesting detective work answering the question.)

In spring 1942, raids for Jews began in southern France, followed by deportation. The situation deteriorated in the following months and the raids were soon daily activities. In September 1942 Julius and Rosie, Karl and Mathias, decided to emigrate to Switzerland. A group of 7 people (including 2 little children) approached the Swiss border and decided to divide into 2 groups in order to minimize the risk of detection. Julius and Rosie, Rosie’s relatives and the children formed one group; Mathias and Karl the other one.

The first group crossed with the help of a Schlepper (guide) a branch of the river Rhone near Geneva. After crossing the river they were stopped by a soldier of the Swiss Army. As he saw the pitiable group he said in broadest Swiss-German: “Eine muess de Afang mache” (Finally, anyone has to start ). Against his explicit orders, he didn’t alarm his superiors but decided to let them in and even explained the best way to the next village inside Switzerland, around 5 km off the border. He probably saved their lives, since at that time refugees usually were sent back after arresting them just at the border.

Karl and Mathias were less lucky. They decided to go on train from Annemasse to Geneva ( a trip of around 20 minutes). In the train there was a raider of the French Police. They immediately were taken out of this train and sent to Drancy. Shortly thereafter both were deported to Auschwitz.

Lotte’s amazing story of survival

One of Toni’s sister — Charlotte (Lotte) — survived the Shoah. Marc Steinfeld did a deep look into her story.

Charlotte Behrer (Brück) was born on 5 Jan 1890 in Vienna. She married Johann Flandorfer, who was Christian. The date of marriage is unclear, but it seems that it was in 1938 or before.

The Nazis had a special law, initiated by Göring, allowing Jews to remain in their homes if they were married to an individual of German descent. This also applied any children of such a marriage. In this case, the child was called a hybrid, but could go on with a normal life. However, if such a marriage ended in divorce or separation, the Jewish member, including children, lost all kinds of racial advantages. In addition, if a child left home, he or she immediately lost all of the advantages. Before 1938, in Vienna, there were relatively many mixed marriages.

In 1938, at the time of the Anschluss, many such marriages were failed and either divorced or separated. In 1939, Charlotte broke with her Jewish faith for reasons that we do not know. It appears that in 1942, at 52 Lotte became pregnant, but the child was stillborn. The Nazis forced the couple to use the middle name ‘Sara’ when reporting the child’s birth and death. (During Nazi Occupation all Jewish wives had to introduce ‘Sara’ into their names).

Charlotte survived as one of very few jews (only around 400 – 600 people) the Shoah in Vienna, we think hidden by Christian friends. She died in 1975 and was buried on the Ottakring cemetery in Vienna. Johann died 1973. Both are in the same grave.

Results for Poland

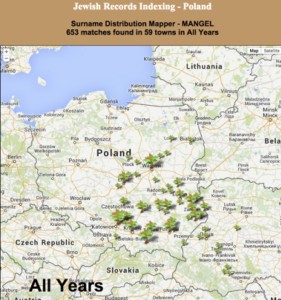

According to JRI there were lots of Mangels in Poland:

I have discovered on Jewish Gen that Max Mangel’s mother was named Miriam (Marjem). Leah Pflugeisen-Kahn born in Tarnow around 1800, but the names of her father and mother are not given.

On to the great-grandparents. Moses Josef Behrer was born 26 November 1854 in Lemberg (now Lviv), son to Jechiel Mechl Benzion Behrer and Sara, nee Brueck (the name Behrer was later changed to Brueck). He married Marjem (Marie) Menkes, born 6 September 1856, in Vienna 3 May 1885. Her parents were Jacob and Chawe Meth. Here are the records of their wedding

Both are listed from Lemberg. He died at age 37 in 1892 and is listed as a hat maker. She died in 1918 at age 62. They are both buried in Vienna.

Karl’s Surname Pflugeisen

Thanks to Thomas Vedel Janhøj (who lives in Copenhagen), I have resolved the question of how the surname Pflugeisen entered into the family and my father end up with it. Marjem Pflugeisen married Markus Mangel, who was a tavern owner in Zbylitowska Góra (a small town about 7 km from Tarnow) sometime before 1876. They had two children, Doba Mangel (30 May 1877 -?) and Isak Mangel (8 Feb 1879-10 Sept 1883) and Marjem was pregnant with their third when Markus died from typhoid fever on 31 Oct 1880, at approximately age 30. T

he next day (1 Nov 1880) their third child was born and named Markus Pflugeisen — presumably the forename in memory of his father and the surname Pflugeisen taken because his mother was a widow without a civil marriage. Also because of that, his birth record shows him out of wedlock. Thus, my grandfather was called Markus Pflugeisen because my great-grandfather and namesake Markus Mangel died before he was born.

My current hypothesis is that Markus was the brother of Max Mangel. According to this hypothesis, Markus Mangel’s son, Markus Pflugeisen and Sol Mangel would thus be first cousins. My current research goal is to verify or refute this hypothesis.

Again thanks to Thomas, I know much more about Marjem. Marjem’s parents were Isak Flugeisen, a tavern owner in Szczepanowice and Dwojra Flugeisen. In addition to Marjem, their children were

- Jente Flugeisen, who married Mordka Dawid Berkelhamer, and had children Izak and Mariem Berkelhamer;

- Chaya Pflugeisen, who married Izaak Holzer, and had children Jacob (who immigrated to the US and died in Newark, NJ in 1935), Urys, Towie, Mozes, Abraham Lieb, Nuchem, Chaim Heinrich, and Szyja Holzer;

- Isak Flugeisen, who married Pesel Kohane, and had children Leib, Cypra, Chana, Symche, Gitla, and Dawid Pflugeisen;

- Rywka, who married Elieser Koretz, and had children Cecilia, Izak, Samuel, Cywie Sure, Hirsch Simche (Zvi Koretz), Rosa, Abraham Leib Jacob, Dawid, Joseph, Ester, Lea, and Gicia Koretz.

Perhaps the most famous of these descendants is Hirsch Simche (Zvi Koretz). The Jewish Virtual Library reports: “He studied in a yeshivah and after World War I went to Vienna to study in the university. After receiving his doctorate, he went to the Vienna Rabbinical Seminary, the Hamburg Institute for Oriental Sciences, and the Berlin Hochschule fuer die Wissenschaft des Judentums. In 1933 he was appointed chief rabbi of Salonika.” He survived Bergen-Belsen and Theresienstadt but died of typhus about 3 months after liberation by the Russians.

I have not yet updated the family tree with this information, but it is clear that all of the action is in a small region around Tarnow:

MATERNAL LINE

David Silver

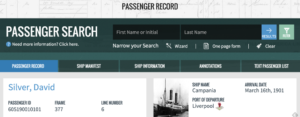

My grandfather was David Silver, who came to the US from Leeds/Liverpool but was born in Russia

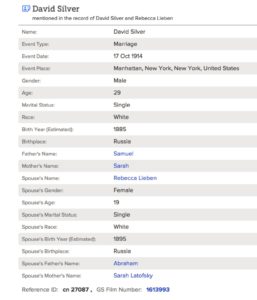

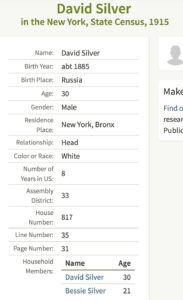

He and Rebecca Lieben were married on 17 Oct 2014 , which is the same day 57 years later that Susan and I were married. I have found Bessie and David in the New York State census of 1915, the year before my aunt Sylvia was born.

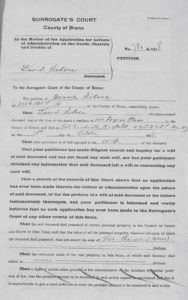

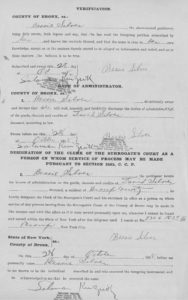

He died in the flu epidemic of 1918, four years and one day after they were married. I have found his probate.

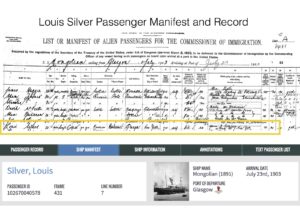

I also think that I have found great-uncle Lou’s passenger manifest and record

Rebecca (Bessie) Leiben Silver

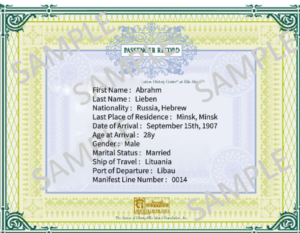

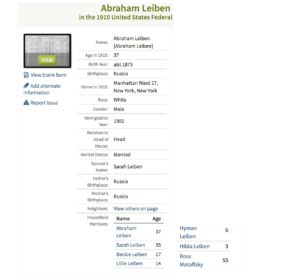

I found the passenger record of our likely great-grandfather Abraham Leiben at Ellis Island

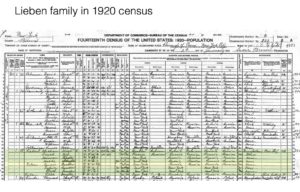

and found the family in the 1910 census: In addition to my grandmother Bessie (Beckie), there are aunts Lillian and Hilda. I do not recall anything about Hyman, who may have died young. I presume that Rose Matoffsky (sic) is Sarah’s mother, based on the marriage information of David and Rebecca above.

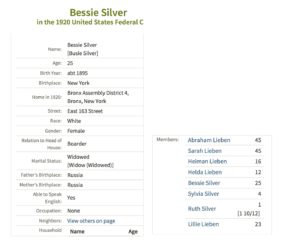

For the Lieben family in the 1920 census, Rebecca is now Bessie, as we knew her, and she, Sylvia and Ruth have moved in with her parents because she is now a widow.

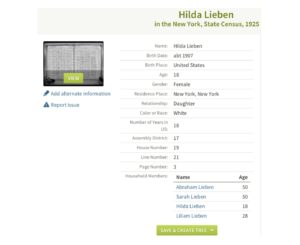

In the 1925 NY census, only Hilda and Lillian are listed as living with Abraham and Sarah. I do not know what happened to Heiman; this is consistent with Bessie having remarried between 1920 and 1922/23.

Abraham and Sarah are buried in Mount Hebron Cemetery in Queens. David Silver is also in Mount Hebron Cemetery in Queens, Block 5, Reference 5, Section D, line 2, grave 1. I have not been able to find photos of any of the other graves.

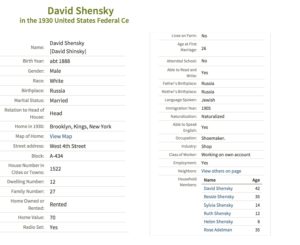

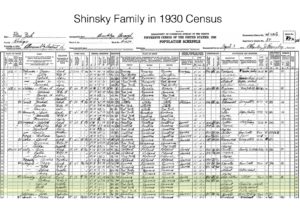

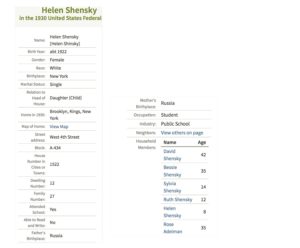

By the time of the 1930 census, Bessie had married David Shensky/Shinksy and had my Aunt Helen, who is 8 years old in 1930. Thus Bessie remarried after the 1920 census but before 1922/3. Sylvia and Ruth are listed with the surname Shenksy, but I do not know if there was a formal adoption or not.

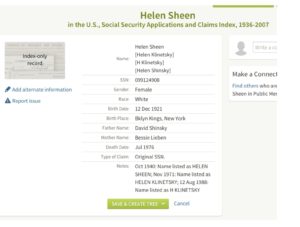

From Social Security records, we know that Helen was born 12 Dec 1921.

I have not been able to find any information about Robert Unger, Bessie’s third husband, but I continue to look for him. In addition, I will continue to look for Lou Silver, his and David’s parents Samuel and Sarah, and more on Abraham and Sarah (Latofsky/Matofsky) Lieben and their children Lillian, Hilda and Hyman.

APPENDIX: KINSHIP RELATIONSHIPS

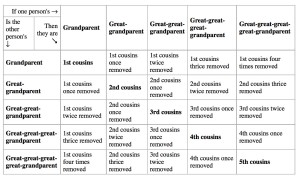

For readers who are wondering about our relationship, the following table from the Wikipedia page on kinship is helpful